Instead of antibiotics

– what are the positive options?

Empowering self-care instead!

Doctors would prefer not to give you antibiotics unless really needed. The hope is to reserve antibiotics for life-threatening bacterial infections. There are three good reasons not to use them for everyday problems:

- antibiotics do not work for viral infections, which are the most common;

- the more antibiotics that are prescribed the more likely we will get infections resistant to them, and may find they are less effective if we need them;

- antibiotics disrupt our natural healthy gut flora (‘microbiome’).

But what can we do instead? If we or our children go down with colds, flu, coughs, sinus, earache or sore throats – or get cystitis or urinary infections – what other options are there? The standard advice is to turn to paracetamol or ibuprofen to relieve discomforts and keep drinking fluids, but does not usually include other options.

In this site we look at simple home-care remedies that have independent evidence for being effective in managing infections, or have a long track record of being useful. They are all safe and mostly cheap.

Before starting check this SAFETY NOTICE. Then consider looking first through the information on home remedies for the common cold. These are often useful for a wider range of infections. Then look at any other symptom you need help with.

Common cold

Cough

Earache

Fever

Flu

Sinusitis

Sore throat

Urinary infection

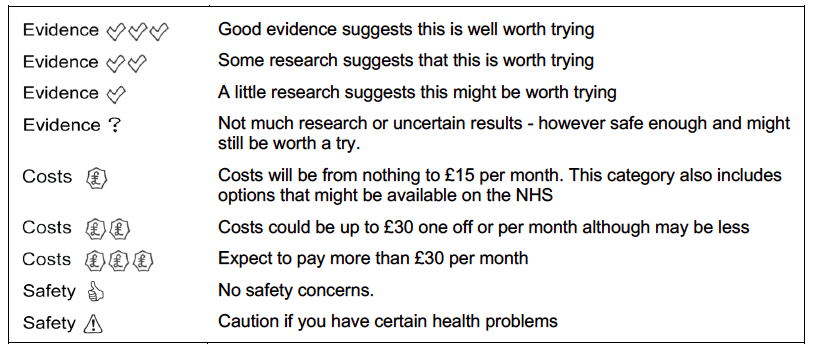

For each treatment option you will see a row with a choice of three symbols. This is what they mean.

The evidence against routine use of antibiotics

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) are one of the most common reasons for consulting in family practice/primary care. Systematic reviews of the benefits of antibiotics conclude that they have little benefit for reducing symptom duration or complications in sinusitis [Ahovuo‐Saloranta. 2014], bronchitis [Smith, 2014], sore throat [Spinks, 2013], and acute otitis media [Venekamp, 2015], and no benefit for laryngitis [Gonzales, 2001] or colds [Kenealy, 2013]. Any limited benefits of antibiotics for ARIs may be further outweighed by unnecessary exposure to common adverse reactions, such as diarrhoea, candidiasis, rash, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea and/or vomiting [Gillies, 2015].

Patients prescribed an antibiotic for respiratory infection may develop bacterial resistance to that antibiotic. The effect is greatest in the month immediately after treatment but may persist for up to 12 months. This effect not only increases the population of organisms resistant to first line antibiotics, but also leads to increased use of second line antibiotics in the community [Costelloe 2010].

In the case of urinary tract infections antibiotic therapy is still the best treatment option. However up to a quarter of sufferers a left with recurrent infections and there are rising levels of antimicrobial resistance [McLellan, 2016; Waller 2018].

There may be other unintended consequences of antibiotic prescription. The recent advent of genome sequencing techniques has revealed the presence of communities of organisms inhabiting many spaces in or on the human body – the microbiota. These appear to have a major influence on the development of immune responses. There is increasing awareness of the importance of the respiratory microbiota in supporting defences, with ‘risk-‘ or ‘resilience-microbiota’ identified, with particular relevance in the vulnerability of children to respiratory infections. For example it has been postulated that children with higher levels of Moraxella and Haemophilus species in their airways during infancy have a higher incidence of ARI in early childhood, while those with more Lactobacillaceae (e.g., Corynebacterium, Alloiococcus) are associated with a lower incidence of ARIs [Hasegawa, 2015]. It seems likely that antibiotic prescription could upset these microbiota.

Delayed antibiotic prescriptions?

In a 2017 update to the Cochrane review comparing different antibiotic prescribing strategies [Spurling, 2017], the authors concluded that where clinicians feel it is safe not to prescribe antibiotics immediately for people with respiratory infections, “no antibiotics” with advice to return if symptoms do not resolve is likely to result in the least antibiotic use, while maintaining similar patient satisfaction. Where clinicians are not confident in using a “no antibiotic” strategy, a “delayed antibiotics” strategy may be an acceptable compromise. There were no significant differences in symptom control and disease complications between the different approaches. Delaying prescribing did not result in significantly different levels of patient satisfaction compared with immediate provision of antibiotics although delay was favoured over no antibiotics.

However explanation of the rationale for delayed prescription is needed [McDermott, 2017] and care taken to minimise mixed messages about the severity of illnesses and causation by viruses or bacteria. Better access is needed to good natural history information, and the signs and symptoms requiring or not requiring general practitioner advice. Significant concerns about paracetamol, ibuprofen and steam inhalation are likely to need careful exploration in the consultation.

Other prescribing options?

Unfortunately standard pharmaceutical alternatives to antibiotics do not sustain research scrutiny well.

For example there is limited evidence to support the agents currently available to treat acute cough due to upper respiratory infection. There are no published, well-designed, contemporary research studies supporting the efficacy of narcotics (codeine, hydrocodone) and over-the-counter oral antitussives and expectorants (dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, chlophedianol, and guaifenesin) [Paul, 2012]. Even the default use of paracetamol and ibuprofen has been shown to be ineffective in managing otitis pain in children [Sjoukes, 2016].

Other approaches may be more productive. Compared to usual care a 2016 meta-analysis indicated that there is moderate quality evidence showing that trained GPs providing written information to parents of children with acute upper respiratory infections in primary care can reduce the number of antibiotics used by patients without any negative impact on re-consultation rates or parental satisfaction with consultation [O’Sullivan, 2016]. A key study reviewed involved 61 practices in England and Wales [Francis, 2009], and the use of an interactive booklet on respiratory tract infections in children within primary care (‘When Should I Worry’). This led to significant reductions in antibiotic prescribing and intention to consult, without reducing satisfaction with care.

In a wider review [Coxeter, 2015], interventions that aim to facilitate shared decision making were found to reduce antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in primary care in the short term by almost 40% compared with usual care, without an increase in patient‐initiated re‐consultations for the same illness or a decrease in patient satisfaction.

It has also been shown that GPs who have had additional training in complementary approaches prescribe less antibiotics than their colleagues [van der Werf, 2018].

SAFETY NOTICE and DISCLAIMER

Infections can be dangerous and should be treated with respect. If there is any reason for concern the first priority is to consult a doctor or other authorised prescriber.

This website is offered to people who are experiencing everyday and familiar infections such as common colds, sore throats, cystitis and other symptoms listed here, and to those who have already seen their doctors for diagnosis.

If there is anything unusual, new or severe, there is unexpected pain, breathing difficulties, weakness, or if your problem lasts longer than its should (see each symptom page for expected duration) do not keep it to yourself: DO CONSULT YOUR DOCTOR. There are particular RED FLAGS to watch out for.

Signs of sepsis: high temperature, cold to touch, severe lethargy (extreme fatigue with immobility), rapid breathing, sometimes skin mottling or blotching that persists under glass pressed onto the skin.

Signs of meningitis: high temperature with headache, stiff neck, sensistivity to light, often skin blotching that persists under glass pressed onto the skin.

Signs of pneumonia (or pleurisy): dry persistent cough, shallow fast breathing and/or breathlessness, fever, rapid heartbeat, chest pains (especially if stabbing chest pains).

Signs of kidney infection (a possible complication of urinary tract infections): pain in flank or elsewhere in the abdomen, high fever, loss of appetite, chills, being sick, diarrhoea.

This website cannot be used to diagnose any condition, nor to substitute for professional care. Every person is unique and unexpected reactions can occur to almost any intervention. The College of Medicine provides this information for the general public based on the best available evidence and professional expertise, but cannot take responsibility for any individual case where this information is used.